Digging for Gold? Asimov and his Sci-Fi background

There’s a widespread convention of considering the period from the late 1930s to the early 1950s as the Golden Age of Science Fiction. Until recently, I couldn’t really judge the era’s output, as I hadn’t read any of its defining works - my own reading path had skipped directly from Wells to Cyberpunk, and then looped back through Philip K. Dick and New Wave material. But now, after having read five novels by Isaac Asimov, I think I have a reasonably clear picture of what Golden Age science fiction looks like.

There’s a pulpy feel to it: tough men in space, straightforward adventure plots, a lot of optimism and a heavy (and interesting) dose of scientifically plausible speculation. What you won’t find much of is character development, psychological nuance, or formal experimentation. My feelings about all this are mixed. Some of it works, some of it doesn’t, and I’m not entirely convinced the luster of the noblest metal which the era borrows for its name is fully warranted.

Take Asimov’s so-called original Foundation trilogy (I say “original” because these books were first published as magazine stories and only later compiled into three volumes in what was, to a large extent, an arbitrary assembly). The trilogy is built around a compelling central concept, partly inspired by Gibbon’s Decline and Fall and partly by the 20th-century rise of statistics, and it develops this premise reasonably well. Still, the characters are flatter then a pancake, mere sketches that barely fulfill the minimum requirements to carry the plot forward. Then again, there’s lots of them, and the interest is in the concept of psychohistory and its implications. wouldn’t it be cool if we could predict the future? How much space would this leave for agency and unexpected, fluke events (book was written before Chaos Theory and the Butterfly Effect made all these fantasies of statistical all-knowingness unlikely, but it still serves as good inspiration for a certain type of person, like the economist and the Effective Altruist).

As for the stories of the original trilogy, they are uneven, but there are flashes of brilliance. One particularly strong arc (mild spoiler alert) is the Mule’s storyline, which spans the second half of Foundation and Empire and the first of Second Foundation. Here, Asimov delivers both a subversion of expectations and a clever narrative device, subtly foreshadowed, that allows the grand plan to resume.

In fairness, Asimov later admitted that after completing the trilogy, he had no desire or ideas to take it further. He did what any sensible writer would do in such a situation: he moved on. But in the 1960s, the Foundation series exploded in popularity and began selling like hotcakes. So the publishers showed up one day at Isaac Asimov’s house with a cartoonishly large bag of money and told him in no uncertain terms, that he was going to write some sequels and prequels. He started with the sequels, which in the 1980s produced Foundation’s Edge and Foundation and Earth. These form a kind of duology, which could be better titled as The Adventures of Golan Trevize. I read the first last year, and the second this year.

Trevize, Spacebound

In Foundation’s Edge, Councilman Golan Trevize is exiled from the First Foundation for publicly questioning the Seldon Plan’s apparent perfection. Officially, he is sent on a mission to investigate whether the mysterious Second Foundation -long thought destroyed- still exists. Trevize suspects that an unseen force is subtly guiding events, manipulating both Foundations. He travels with historian Janov Pelorat on a search for the long-lost planet Earth, believed to be humanity’s origin. Meanwhile, the Second Foundation, hidden and composed of mentalics, secretly works to keep the Plan on track and views Trevize's quest as a potential threat.

The journey ultimately leads Trevize to Gaia, a planet where all life and matter are part of a single, unified consciousness. There, Trevize is presented with a choice: support the individualistic First Foundation, the manipulative Second Foundation, or Gaia’s vision of a future galactic supermind called Galaxia. Trevize chooses Gaia, believing it offers the best hope for a peaceful and stable future, but he remains unsure of his instincts, and vows to find Earth to confirm whether his choice was right.

In some ways, Foundation’s Edge conforms to the classical standards, but it is clearly a weaker piece. It shares the flatness of characters and aversion to description - even after having finished this and its successor, I have literally no mental picture of what Golan Trevize looks like, except ‘young, daring and handsome’. The Gaia plot twist seems like a very lame attempt at replicating the Second Foundation twist in a way that reminded me of The Return of the Jedi with its (“now bigger and better!!”) Death Star 2. The novel is relatively big compared to the first ones (but soon to be dwarfed by the almost 500 pages of its continuation) but it does its job decently in spite of its limitations, like (again) Return of the Jedi.

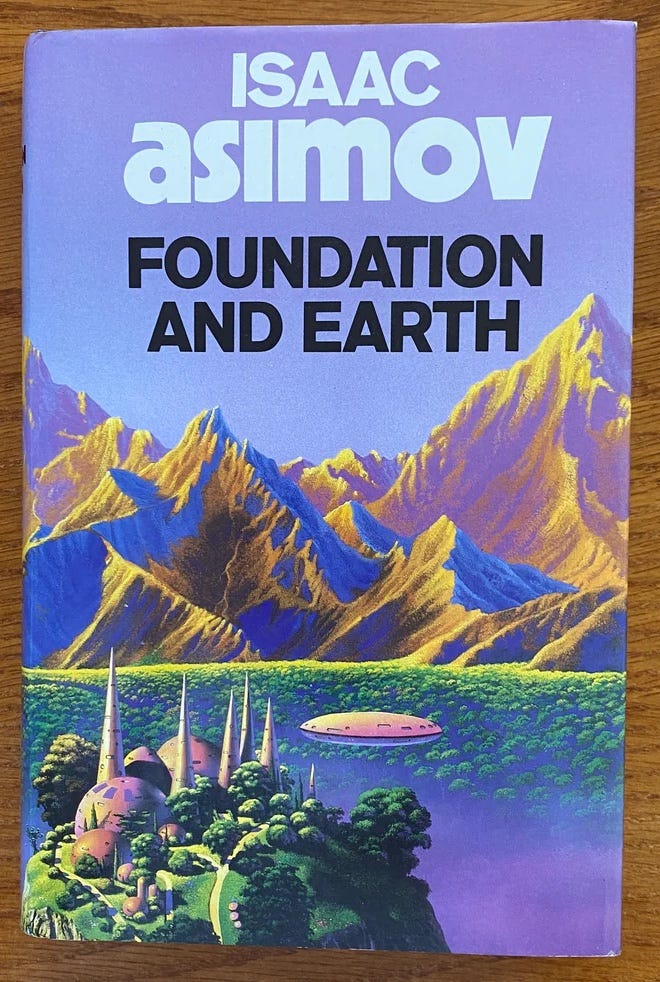

All these defects continue (and are compounded with a ludicrous level of rambling) in Foundation and Earth , were Golan Trevize continues his quest to find the lost planet Earth, hoping it will help him understand and justify the momentous decision he made about humanity’s future in the previous novel. He’s travelling again with Janov Pelorat and the latter’s young, sexy, Gaian partner and psychic mind reader extraordinaire Bliss in a series of journeys across several planets, uncovering fragments of humanity’s forgotten past and encountering a variety of cultures and ideologies (and genders! Quite an unexpected turn to see Asimov dealing with hermaphrodites). The novel blends exploration, philosophical inquiry, and political intrigue, gradually building toward a revelation that may reshape the course of galactic civilization. If you thought Foundation’s Edge was sometimes verbose, here you will get tired to death of the repeated disquisitions of the advantages and disadvantages of individualism versus collectivism, and of the overall circularity of dialogues. Most of the adventures and planetary experiences are… meh1, and have some really outdated ways of solving conflicts and pushing the narration forward, with Trevize donning occasionally the role of Multiplanetary Casanova, solving diplomatic impasses and information bottlenecks with the ease of a handsome galactic bachelor whose main tool of persuasion seems to be his bedroom skills.

Foundation and Earth tries to be a grand philosophical sequel, a journey into the buried past of humanity and a meditation on its possible futures. It also tries to include easter eggs, tie-ins to other series and all the fan service that we are accustomed to expect in modern and successful mass culture series (I’m looking at you again, Star Wars). Still, while it often gets bogged down in repetition and features episodic storytelling that can feel uneven or dated, it remains moderately entertaining. Asimov’s curiosity about ideas and his ambition to tie the series into a unified narrative arc give the novel a certain momentum. For readers who have come this far, it’s a necessary read -if not for its pure literary merits, then at least to witness how the sprawling Foundation mythos is brought toward a kind of closure. But if you’re a more casual and less committed reader, you’re probably better of just sticking to the original trilogy.

I mean… come on, Isaac… the terror of the dog pack? The horror of the sticky moss? Give me a break…