Eternal Return

It's back again to Bartle and Sherbert!

Somewhat more than a year ago, I was writing here about my progress with Bartle and Sherbert’s 3rd edition Introduction to Real Analysis. I then had to make a big hiatus, due to work, family obligations and other reading projects (including another math textbook I was reading at the time: Halmos’s Naive Set Theory).

A couple months ago I decided I now had the time to return to it and make it my math-textbook goal for 2026, so I’ve been reading it again from scratch and doing all the exercises again. Perhaps I shouldn’t try to do all of them, as this slows me down tremendously: they don’t come with indications of difficulty, and I sometimes spend over an hour trying to untangle one and getting really frustrated in the process. Math is hard. It might be the case that I am too dumb for this, but I get some solace from the fact that even for professional mathematicians, the subject is never a cakewalk.

Yesterday I finished redoing the exercises from section 2.4. Reading back, another thing I find frustrating is that I hit the same stumbling blocks again -I spent a whole morning stuck with 6 until I read the note-to-self I had written about it in June 2024-. And looking at page count, exercises from 2.3 occupy just 8, while this one was 21, which gives an idea of the detail, complexity and verbosity required. The Arquimedean Property, Suprema and Infima of functions and density of different subsets of Real Numbers can be a lot of work…

Anyway, let’s hope there’s no more stops and I can finish this before the end of 2026, which I am doubtful of. For one, I proceed at snail’s pace. And besides, I was thinking of alternating B & S with the corresponding chapter in Abbott’s Understanding Analysis. We shall see…

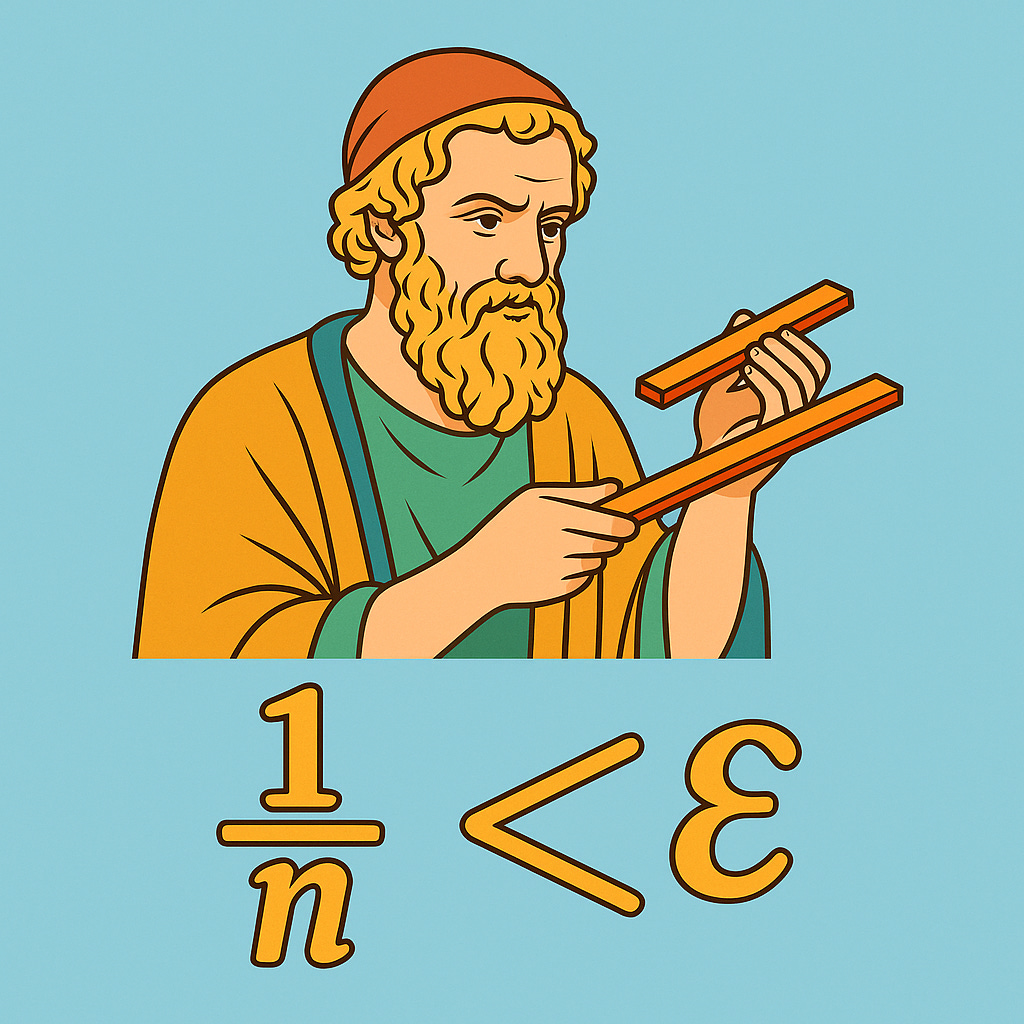

If you haven’t studied Real Analysis, you might we asking yourself ‘What the heck is the Archimedean Property’ that Manuel’s prattling about (that is overtly optimistic; a more likely scenario is that you’re just ignoring this post), so let’s wrap up this post with it. The Archimedean property states something very intuitive but which can’t be proven without the Axiom of Completeness: that for every real number x there exists some natural number n_x such that n_x > x1. But the way it is formulated in the book sounds very non Greek to me, which made me think about what was it that Archimedes was actually trying to prove. I discovered, after a brief search, a much more Classical/Geometric formulation of the problem, as follows:

Given two magnitudes (a and b), repeating any one of them a sufficient number of times will give you a length greater than the other one.

And yes, this *does* feel like something Archimedes would want to prove: it rules out infinitesimal or infinite magnitudes in the Greek geometric sense. Algebraically, you would state this as “∀ a,b > 0, ∃n ∈ N such that na > b”. And then yes, if you take the special case a=1 and rename b as x and n as n_x (it’s a natural number whose choice depends on the value of x), you get the initial formulation.

It is interesting to remember that for the Greeks, after Pythagoras, it was understood that ‘numbers’ and ‘magnitudes’ (lengths, areas, and volumes) were a completely different kettle of fish. Weird as this feels for us take, it makes sense: with magnitudes you can easily create things like ratios of natural numbers (even though Greeks also considered these as relations between numbers, not as numbers in themselves), i.e., Rationals, but also Irrationals, like √2 and π, which they called ἄλογοι, “without ratio”, “inexpressible”.

As for the name, the Archimedean property seems to have been baptized thus by Karl Weierstrass and Richard Dedekind, who recognized that Archimedes’ ancient axiom captured a fundamental feature of the real number system.This naturally makes one think about non-Archimedean fields, which would be ones containing infinitesimals, like the Hyperreals, and which in many respects are so intuitive to think about when thinking about Calculus.

There are other corollaries derived from this formulation of the Archimedean Property which in (textbook) practice are much more useful, like ‘for every ε > 0 there exists some 1/n, the specific n depending on the ε, such that 0 < 1/n < ε. Deriving them is just a question of making some algebraic fidgeting.